Please join us for the Autumn 2022 CMRS Symposium: "Environments and Sustainability in the Medieval and Early Modern Worlds"

This in-person event will take place in Thompson Library, Room 202, with breaks next door in Thompson Library, Room 204. Nearby parking for visitors is available at the Tuttle Garage and Ohio Union South Garage.

Schedule of Events

Friday, November 18, 2022

8:30-9:00AM: Registration

9:00-9:15AM: Director's Welcome

9:15-10:00AM: Paper 1

Sugata Ray (History of Art, UC Berkeley)

‘How to See Water in an Age of Unusual Droughts: Ecological Aesthetics in the Little Ice Age, India (ca. 1550–1850)’

The Little Ice Age (ca. 1550–1850), a climatic period marked by glacial expansion in Europe, brought droughts of unprecedented intensity to South Asia. In drought-ravaged north India, the beginnings of the Little Ice Age not only corresponded with the emergence of new techniques of landscape painting and riparian architecture that emphasized the materiality of flowing water but also saw the enunciation of a new theology of Krishna worship that centralized the veneration of the natural environment. Tracing the intersections among artistic practices, theological economies, and the ecocatastrophes of the Little Ice Age, my talk aims to generate an ideation of an eco art history that brings together the environmental and the aesthetic.

10:00-10:45AM: Paper 2

Hillary Eklund (English, Loyola University)

‘Imagining Land and Water in Colonial Mexico’

In the sixteenth century, Spanish explorers recorded with admiration the extraordinary skill of water management practiced in the Mexica capital of Tenochtitlan, a city built on a network of lacustrine islands. Less than a century after their war of conquest leveled the city’s floating gardens, canals, and causeways, the colonial government made plans to drain the lake basin entirely. How might we reconcile these seemingly opposite positions? Eye-witness accounts of the conquest and early maps claim a measure of Hapsburg control over the conquered Mexica city, but they elide both the chaos of colonial war and the erosion of the Indigenous knowledge that made Tenochtitlan so remarkable to begin with. Subsequently, as the newly Spanish administrative center suffered from its own terrible success, worsening floods fueled ambitions to drain the lake basin. In characterizing amphibious spaces as hostile obstacles, and even opportunities to demonstrate Spanish fortitude, the colonizers denied the interdependence of land and water and undermined the interlinked social, religious, economic, and political systems that secured human habitation within that dynamic ebb and flow. Situating this colonial episode within a broader global hydrological story, this talk considers how human habitation happens at variable points on a continuum of world-shaping control, and how the discursive fields of humanist climate studies and the Anthropocene might better attend to these distinctions.

10:45-11:05AM: Discussion

11:05-11:15AM: Break (Thompson 204)

11:15AM-12:00PM: Paper 3 & Discussion

William Cavert (History, University of St Thomas)

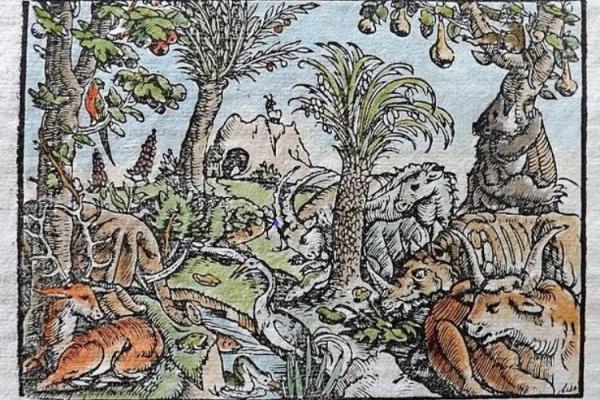

‘Early Modern Anthropocentrism in Theory and Practice: the Case of Animal Killing’

It has been generally agreed that the conception of humanity's relationship with nature in Early Modern England can usefully be summarized as anthropocentric, with scripture explaining how the world and its creatures are part of a divine plan with people at its center. Recent scholarship, however, has qualified this picture, showing how philosophers and poets ruminated on animal intelligence and subjectivity, often seeing them as more than simply tools for human needs. But a problem emerges when we read such writing against the mundane killing of animals that occurred across society. At the hunt and down on the farm, people killed creatures both domesticated and wild, both to eat and for sport, those they carefully reared and those they considered vermin. In all cases animal killing was not only considered acceptable, but a key practice through which societies were constituted and ordered.

1:30-2:15 PM: Paper 4

Luke Wilson (English, OSU)

‘Kind of Cruel’

The idea of the tree as an individual entity separable from the forest of which it was a part must have emerged very early on. Seeing the tree for the forest presumably involved a process of differentiation that repeated itself as cultural and material conditions changed. If on the one hand this process brought a domestication in which the tree became a familiar and even friendly presence, on the other it invested the tree with qualities that eluded human control and posed simultaneously a promise and a threat. This talk argues that this split response to the differentiation of tree from forest informed the fetishism of the tree emergent (or at least newly prominent) in England in the early seventeenth century. Keith Thomas remarks that over the course of the century trees acquired “an almost pet-like status” even as modern notions of the pet animal also emerged. Unlike animal pets, pet trees, owing in part to their longevity relative to that of human beings, resisted their complete domestication; they gestured beyond the human in mysterious ways. Despite but also because of its immobility, its rootedness, the tree became an especially complex expression of the human ability to exert control over the natural world and the limitations of that ability. It also had become uniquely suited to the figurative expression of familial, political, and social relationships defined in terms of rootedness in a singular origin, branchedness, and continued vitality. These developments occurred together with a heightened concern over deforestation in England in the later Tudor and Stuart periods, a perception that trees collectively, trees as a resource, were under threat, and with them the integrity of the nation. My talk brings to bear these intertwined but separable histories of the part and the whole, of the tree and the forest, on a series of poetic encounters between persons and trees that emphasize empathy or fellow-feeling between the two, but turn out, again and again, to be predicated on a cruelty through which that fellow-feeling is produced. In the poetry of Amelia Lanyer, Mary Wroth, Andrew Marvell and others, the tree, at once assimilated to and resisting human meaning-making, functions as an energetic center around which human relations shape themselves.

2:15-3:00PM: Paper 5

Keith Pluymers (History, Illinois State University)

‘Green Imperialism Revisited’

What was the relationship between the development of sustainability and English colonial expansion in the early modern period? Historians have pointed to the early modern period as a crucial early phase in the development of sustainability as a concept, even if it would, some argue, only emerge in recognizable form in the eighteenth century. This was, however, also the period in which European colonial expansion accelerated. Scholars like Richard Grove have connected these two developments by identifying colonial resource management and natural philosophical projects as key sources for conservationist thought. This talk addresses the relationship from a different angle, arguing that early modern English colonial promoters, agricultural improvers, and government officials debated whether colonial expansion supported careful management of natural resources in England for posterity.

3:00-3:20PM: Discussion

3:20-4:00PM: Break (Thompson 204)

4:00-5:15 PM: Keynote and Discussion

Kimberly Borchard (Spanish, Randolph-Macon College)

‘Appalachian and Apalachee Environments in the Renaissance and Today: Historical Precedents and Contemporary Struggles'

Today, the words “environment” and “sustainability” conjure the specter of twenty-first-century climate change and its implications for human survival. Yet the mechanisms of the current environmental crisis, as well as the humanitarian catastrophes that it threatens to unleash across the globe, were set into motion centuries ago by the processes of European settler colonialism, extractive mining, and the theft of land traditionally stewarded by Indigenous populations. At a speech delivered in April 2022 at a symposium on the missions of Spanish Florida, Chief Arthur Bennett of the Talimali Band the Apalachee Indians of Louisiana[1] made the following statement:

The government is willing to spend millions of dollars saving endangered animal species and protecting the endangered animals’ habitat. Are Apalachee Indians not as important as these animals? The state of Florida owns thousands of acres of land used for growing trees to sell. How many trees can equal the life of one Apalachee? Are we not worth as much as a pine tree?

Although the Apalachee never mined gold, the European belief that they did served as a catalyst for generations of attacks that eventually displaced them from their ancestral lands in Florida and left them stranded in central Louisiana until this day. After providing an overview of the quest for Apalachee gold, which led to the invention of early modern Appalachia as a colonial frontier ripe for European mining and environmental exploitation, I will share some of the new projects that have been occasioned by the publication of my research. These projects include a critical study of the testimony of two Native women who claimed in 1600 that the Appalachian Mountains were littered with diamonds and gold, as well as a new monograph on the plight of the Apalachee since 1763. Together, these projects provide a glimpse of unknown Appalachian and Apalachee history, the impact of that history on the present, and the ways in which historical knowledge may be used to help the Apalachee in their current struggle for tribal sovereignty.

[1] The unusual syntax of the tribe’s name is the result of an ongoing lawsuit and trademark dispute.

Saturday, November 19, 2022

10:00-11:30AM: Roundtable Discussion