Sometimes, two very different areas of life converge in such serendipity that you just have to see how it plays out. This is what happened last May when I found myself in Florence, Italy marveling at Renaissance art and spending hours in a small sun-drenched dance studio with eight other dancers from Flux + Flow Dance and Movement Center in Columbus.

When studio owners Russell and Fili announced the trip, I knew three not altogether compatible things: 1) it would be an absolute dream, 2) I could definitely not afford it on a grad student’s salary, and 3) I had to go. I’d heard that, for the last trip, a couple dancers had gotten grants to tie the trip to their work and/or research, which made me wonder if I could do the same.

The dance component of the Florence trip would involve taking the visual art of the sculptures and paintings of the Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze, Uffizi Galleries, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, and Museo Nazionale del Bargello and transforming it into performance art. While I had no idea what exactly this would look like, I thought the process would be fascinating to look at as a kind of embodied translation of Renaissance artifacts into contemporary dance.

My main research focus in graduate school has been on early modern women’s religious writing and interpretation, but I arrived there, in part, by way of an enduring fascination with religious translation. I’ve found a kind of strange comfort in the instability and subjectivity inherent to acts of translation. Once you realize there is no such thing as an easy transfer of meaning between systems of signs, be they linguistic, visual, physical, or otherwise, you let go of some weighty things: the duality of accurate and inaccurate, the assurance that you must find “the one way.” And because there isn’t really a “right answer” to translation, I have seen so much creativity play out in the endless attempts to carry across meaning from a source to a target “text.” Further, the interpretation of meaning necessary to translation is by nature filtered through an individual’s subjectivity. I’ve found the ways that people’s identities stick to their creative outputs as they navigate the complexities of transferring meaning fascinating and humanizing. But because I study Renaissance literature, I never get to see this navigation play out in real time. I see the products, yes, but only guess at the process.

A week participating with a group of people in creating via inspiration and interpretation seemed like the perfect way to see a version of a translation process using Renaissance artifacts. This is what I described in my grant application for the Office of International Affairs’ International Research and Scholarship Grant. With their generous grant, I was able to afford the trip to Florence and participate in a unique sequence of translational acts that were heavily and intentionally formed by our own experiences of ourselves as individuals, the community we created, the Renaissance art around us, and our current cultural moment.

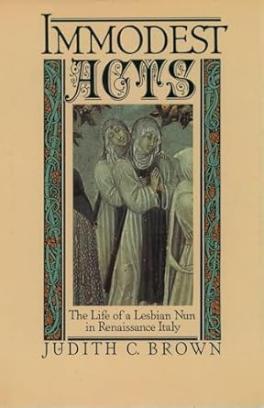

Russell came into the trip with some of his own thoughts, research, and inspirations. In preparation for the first such trip (taken in October 2023), he’d gotten recommendations from Professor Karl Whittington (History of Art) on some materials to read about queer art in Renaissance Italy, which was Russell and Fili’s initial main theme for the trip. Russell in particular also became very interested in Benedetta Carlini, the Italian Catholic nun and mystic who, as abbess, had a lesbian relationship with one of her nuns. In preparation for the trip, Russell asked us to read Judith C. Brown’s Immodest Acts, a remarkable work of public-facing historical scholarship about Benedetta published in 1985. Her story gave us a devotional, mystical, subversive, and morally ambiguous framework to ponder, as several of us did in the evenings. These conversations alone reminded me how the period and people I study can facilitate deep reflection in ourselves and our communities in the present, both via similarity and via tension.

In the beginning of our trip, a few things happened organically that came to further shape the trajectory of our art:

- A group that was initially meant to be eight (not counting studio owners and leaders Russell and Fili) turned to seven. We lost the only male participant on our trip, leaving us with seven women of differing ages, experiences, and backgrounds.

- We arrived at the villa where we were staying to see an icon of Our Lady of the Seven Sorrows: Virgin Mary with seven swords stuck into her heart.

- On our first day touring Florence, we had to delay our entrance to the Accademia, so Fili led us on a walk around a random nearby neighborhood, where we happened to see “brucia il patriarcato” (“burn the patriarchy”) spraypainted on a wall. They immediately had us seven women pose around the message in triumphant laughter.

We’ll return to these ideas later

At the Accademia, we were charged with finding art that reflected “devotion,” which we were to send to Russell and Fili by the end of the day. Portrayals of devotion in its varied contexts were where Russell wanted to begin as he’d been further mulling over queer religious art and Benedetta. He’d also been hearing about our wine drenched conversation from the previous night in which we had dubbed ourselves “The Seven Sisters of the Seven Swords,” in homage to the patron saint of our lodging.

In the studio the next morning, he first brought our attention to a painting by Francesco Salviati. I had sent in this painting to the group chat because I had been struck by the maternal devotion depicted there, a subject frequently on my mind as the mother of a four-year-old. Russell said, “We’re going to recreate some of the shapes and movement we see in these characters, but I think we’re going to do it with swords.” The juxtaposition of tenderness and weaponry led to friction. Not everyone was comfortable with this. So, we asked questions to navigate it: Are there times when care and violence coincide? Devotion and violence? Does the sword have to be violent? We would go on to navigate this tension throughout the rest of the week, sometimes as a group at the studio, sometimes looking at the stars and wondering how much people in the Renaissance were really like us. As the resident Renaissance scholar, I got a lot of questions, some that were easy to answer (“Why do we keep seeing King David everywhere?”) and some that were complex, requiring an intense kind of cross-temporal and cross-cultural empathy (“Why did their religion influence them so much?”).

Left: Madonna and Child, the Young St. John and an Angel (1543 – 1548) by Francesco de’ Rossi Salviati Cecchino at the Galleria dell’Accademia di Firenze; Right: All seven dancers posed as the Madonna, though rather than holding Jesus, we are holding our swords.

Two days later, in the Uffizi, we were instructed to find instances of “sevens” in the museum, as there were seven of us. We all found a series of seven paintings by Sandro Botticelli and Piero del Pollaiolo of the Seven Virtues of Christian tradition. We enthusiastically forwarded them to the group chat. We would later each be assigned a virtue that we would embody in a living tableau that moved between different themes. Mine was Fortitude.

Left: Fortitude by Sandro Botticelli (1470). Center: Temperance, Faith, Charity, Hope, Justice, and Prudence by Piero del Pollaiolo(1469–1472) . Right: All seven dancers replicating their virtue.

Also at the Uffizi, Russell suggested we make sure to stop by Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Beheading Holofernes (1620), which we did. In the studio the next morn ing, we discussed Judith and her maidservant Abra in the painting, how they were active and unified in their shocking act of liberatory violence against Holofernes. From there, we did an exercise in which folding chairs (pretty much the only props available in the studio) became each of our personal Holofernes. By turns, we each acted as Judith with the other six as Abras in support of us lifting (in slow motion) a chair and crashing them into a pile in the center of the room: a pile of defeat.

These may seem like disjointed accounts, which is exactly what they are and exactly what our process ended up being. We shared a number of very different thoughts, feelings, experiences, images, and exercises and wondered how they might all come together.

And yet they did! On our last morning, we performed a twenty-minute piece that explored how individuals with their own histories and their own darkness come together to pursue joy by purging our demons with the help of our sisterhood. There was no audience. Just us. Unlike the paintings and sculptures that were our inspiration, which had been seen and interpreted by millions across the centuries, ours was private, ephemeral, much like that of so many more artists that came before us (including many of the women I study).

I’m still not entirely sure what this all says about translation. I’ll be working that out (hopefully in article form) in the months to come. I experienced this particular artistic translation as a cumulative, serendipitous, personal-yet-communal, trial-and-error process. I experienced it as reaching for feelings and moments and emotions and images and words and ideas, doing what we could to adjust them to a new container and never succeeding entirely but always making something lovely. I think that is often what translation is: reaching for something and seeing how it manifests in your hand as it changes form across the reaching; making something new and lovely that pays homage to its source as it clashes with new contexts. It’s more than transferring meaning; it’s giving breath to a new creature hidden in the source but awaiting the person or people who can awaken it. What a worthwhile process to be a part of.

Elise Robbins, PhD Candidate, Department of English