Symposium Spotlight the Maritime Humanities of the Medieval and Renaissance Worlds

The recent symposium, Exploring the Medieval and Renaissance Maritime Humanities, brought together scholars and community members for a thought-provoking exploration of maritime cultures, histories, and environmental challenges. Featuring five distinguished speakers, the event examined the complex and multifaceted relationships between humans and the sea, spanning from monastic communities and medieval massacres to artistic representations and early commercial fishing industries.

The symposium began with Professor Ellen Arnold (History, OSU)’s presentation, Saints by the Sea: Faith, Fear, and Forgiveness. Professor Arnold explored miracle stories from coastal monastic communities, focusing on Noirmoutier, Lindisfarne, and the tidal bores of the Garonne River. She highlighted how these liminal spaces offered both opportunities and unique risks for monastic life. Rivers, she noted, are both semi-permanent features and subject to natural fluctuations, a concept illustrated through the Garonne River’s tidal bores, which carry saltwater far inland. These bores, she explained, were not uncommon and still occur today, as demonstrated in a video she presented showing people surfing the waves they create. A

striking example she discussed was the mass stranding of 237 dolphins at Noirmoutier, which underscored the complex interplay of fragility and survival. The monks at Noirmoutier, suffering from famine and on the brink of failure, saw the event as divine intervention, reinforcing their belief in providence. She also examined Lindisfarne, an island that becomes separate from the mainland twice a day, which served as a case study for the dynamic interplay between monastic isolation and environmental interconnectedness. Monastic communities, she argued, were deeply tied to their surroundings, relying on natural resources while simultaneously being shaped by the unpredictability of the sea and tides.

Professor Amanda Respess (History, OSU Marion) followed with her talk, Sea Change: An Indian Ocean Case Study of Continuity and Rupture. She examined the repercussions of the 1366 massacre of Quanzhou’s Muslim community on global trade and maritime routes, tracing the broader shifts that followed in the Indian Ocean world. Before the massacre, Quanzhou was home to a thriving Muslim population with six to ten active mosques, a testament to the Mongols’ policy of privileging certain hereditary groups. The Mongols had created a caste-like hierarchy that placed Muslims in key administrative and economic positions, which both facilitated trade and made them targets for resentment. However, as political shifts weakened the status of Muslim judges and removed tax exemptions, tensions escalated. The massacre marked a violent rupture in centuries of coexistence. Mosques were destroyed, graves were uprooted, and survivors were forced to flee, many by sea. This event led to a dramatic reconfiguration of Indian Ocean trade, with new centers emerging in Ayutthaya and Malacca. Professor Respess drew on evidence from the Takashima 1 and 2 shipwrecks, which contained Chinese and Southeast Asian ceramics, as well as gunpowder weapons, to illustrate how trade adapted in response to the shifting political and religious landscape. Additionally, she discussed how European ceramicists sought to replicate the medical and aesthetic qualities of Asian drug jars, reinforcing the growing global demand for Eastern commodities and medicines.

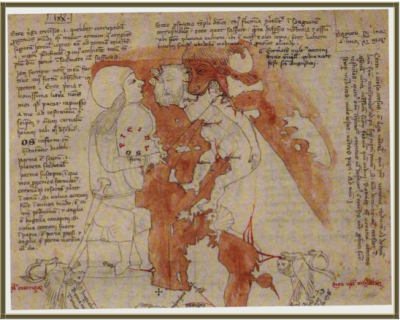

The third presentation, Opicinus de Canistris’s Demonic Seas, was delivered by Professor Karl Whittington (History of Art, OSU). His talk examined the visually arresting and highly idiosyncratic maps created by the fourteenth-century priest Opicinus de Canistr is. These maps, based on portolan charts, depicted Europe and Africa as gendered human figures, while the Mediterranean Sea was represented exclusively as a demonic force. Professor Whittington argued that Opicinus’s works reflect the multivalent nature of the sea as both a site of danger and a space for travel and commerce. He noted that while portolan charts were highly accurate navigational tools, Opicinus used them to depict a symbolic geography where the sea was a source of corruption and unknowable horrors. His striking use of red ink emphasized themes of pollution and moral decay, visually reinforcing the negative perception of the sea. He also explored how Opicinus incorporated biblical references and demonic imagery into his maps, highlighting the ways in which medieval thinkers associated the ocean with chaos and moral disorder. Additionally, Professor Whittington addressed the broader implications of medieval understandings of the ocean, particularly in light of the era’s limited knowledge of its depths. He reminded the audience that, for medieval Europeans, the sea was an unfathomable abyss, a space whose dangers and mysteries were largely speculative rather than empirical.

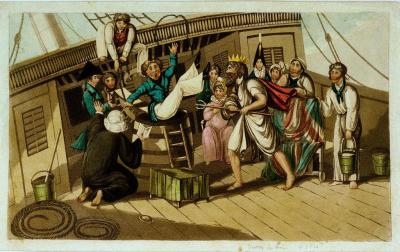

Professor James Seth (English, Central Washington University)’s presentation, World Upside Down: Early Modern Maritime Theatre and the Carnivalesque, examined the theatrical traditions of early modern sailors, focusing on the ways performances aboard ships not only entertained but also reinforced social cohesion and discipline. Seafarers engaged in various forms of shipboard theatre, ranging from scripted plays to spontaneous commemorative performances. These theatrical events were often tied to feast days, visits from dignitaries, or significant moments in a voyage. The most significant of these was the crossing the line ceremony, in which sailors crossing the equator for the first time underwent elaborate and often humiliating initiation rites. These rituals, Professor Seth argued, mirrored the land-based carnival tradition, temporarily upending hierarchies before ultimately reaffirming them. The performances, which included mock trials, knighting ceremonies, and full immersion in seawater, served to strengthen bonds among sailors while preparing them for the psychological and physical challenges of long voyages. He also highlighted how these traditions varied across different maritime cultures, noting that English, French, and Dutch sailors all had unique variations of these ceremonies. Despite their differences, the overarching themes of subversion and reaffirmation remained consistent, demonstrating how performance and ritual played a crucial role in maintaining order at sea.

The final speaker, Professor Richard Hoffman (History, York University, Canada), delivered All the Fish in the Sea?, an insightful exploration of medieval European fishing practices and marine resource management. He emphasized tha

t medieval societies, despite their reliance on the sea for navigation, had only a limited understanding of its potential as a food source. Early fishing efforts focused primarily on freshwater and inshore species such as eel, salmon, and herring. The so-called marine fisheries revolution of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries saw the expansion of commercial fisheries targeting cod, hake, and sardines. However, Professor Hoffman cautioned against the assumption of infinite abundance, pointing out that environmental changes and overfishing had long-term consequences. He highlighted the challenges of reconstructing historical fishing practices, noting that certain species, such as tuna, left little archaeological evidence due to the nature of their processing. He also discussed how changes in land use, such as deforestation and agricultural expansion, had unintended consequences on fish populations by altering water quality and spawning grounds. He concluded by emphasizing the adaptability of medieval fishing communities, who developed new technologies and methods in response to shifting ecological conditions and market demands.

The symposium provided a compelling interdisciplinary look at the medieval and Renaissance maritime world, offering fresh insights into how societies navigated, exploited, and conceptualized the sea. By bringing together history, art, archaeology, and environmental studies, the event underscored the enduring significance of maritime humanities in understanding past and present human interactions with the ocean.