A graduate goes on a quest for love.

It’s February, so the whole world is covered in pink and red hues, and everywhere you turn, it’s chocolates and hearts. As someone who spends most of her time in courtly literature reading about the love between knights and ladies, I decided to do some research to see how love was represented elsewhere in the Middle Ages?

I first started my journey by thinking about who famously wrote about love. I turned to Professor Sarah-Grace Heller, who told me that if there was a group of people who really knew love, it was the Troubadours. She lent me her copy of Lark in the Morning: The Verses of the Troubadours, edited by Robert Kehew. She pointed out one of her favorites!

The following is the text in the original Occitan with a facing English translation.

Ab la dolchor del temps novel

Foillo li bosc, e li aucel

Chanton, chascus en lor lati,

Segon lo vers del novel chan;

Adonc esta ben c'om s'aisi

D'acho don hom a plus talan.

De lai don plus m'es bon e bel

Non vei mesager ni sagel,

Per que mos cors non dorm ni ri,

Ni no m'aus traire adenan,

Tro que sacha ben de fi

S'el es aissi com eu deman.

La nostr' amor vai enaissi

Com la branca de l'albespi

Qu'esta sobre l'arbre tremblan,

La nuoit, a la ploia ez al gel,

Tro l'endeman, que.l sols s'espan

Per la fuella vert e.l ramel.

Enquer me membra d'un mati

Que nos fezem de guerra fi,

E que.m donet un don tan gran,

Sa drudari' e son anel:

Enquer me lais Dieus viure tan

C'aia mas manz soz so mantel.

Qu'eu non ai soing de lor lati

Que.m parta de mon Bon Vezi,

Qu'eu sai de paraulas com van,

Ab un breu sermon que s'espel,

Que tal se van d'amor gaban,

Nos n'avem la pessa e.l coutel.

Such sweetness spreads through these new days:

As woods leaf out, each bird must raise

In pure bird-latin of its kind

The melody of a new song.

It's only fair a man should find

His peace with what he's sought so long.

From her, where grace and beauty spring,

No word’s come and no signet ring.

My heart won't rest and can't exalt.

I don't dare move or take a stand

Until I know our strife’s result

And if she'll yield to my demands.

As for our love, you must know how

Love goes- it's like the hawthorne bough

That on the living tree stands, shaking

All night beneath the freezing rain

Till that next day when that warm sun, waking,

Spreads through green leaves and boughs again.

That morning comes to mind once more

We too made peace in our long war;

She, in good grace, was moved to give

Her ring to meet with true love’s oaths.

God grant me only that I live.

To get my hands beneath her clothes!

I can't stand their vernacular

Who'd keep my love from me afar.

By way of words, I guess I've found

A little saying that runs rife:

Let others mouth their loves around;

We've got the bread, we've got the knife.

This poem, attributed to Guillem, the seventh count of Poitiers (1071-1127), is one of the earliest known examples of Provençal poetry. He was one of the wealthiest and most powerful men of his time, with lands far exceeding the royal territory around Paris. Though he took part in the First Crusade, his fame rests chiefly on being the first known poet in the Provençal language whose works have survived. Eleven of his songs remain today, and this one is perhaps his loveliest. The poem starts with beautiful imagery of spring, birdsong, and new growth. However, not all is happy, as Guillem references a fight with his lady. Yet they reconcile, and she gives him a ring as a token of their love. He ends the song with hopes for the future.

I read the poem aloud to myself, enjoying the way the rhymes rolled off the tongue. Of course, I remembered that these songs often had accompanying music. Given that little remains of the Troubadours, it should come as no surprise that their melodies survive even less. I know that we have surviving musical notation, I’ve seen it is surviving hymnals but what did a medieval love song sound like? Was it like our modern ballads? Did it have a chorus you couldn’t help but sing? There was only one logical person to turn to: Professor Graeme Boone.

He told me that if I was on the hunt for all things Valentine, there was no greater musical manuscript than the Chansonnier Cordiforme. This beautiful heart-shaped book was created in the 1460s for an upper-middle-class cleric in northern France. It is essentially a book of love songs. Professor Boone sent me an image of a particularly charming page featuring an adorable couple in matching outfits. Talk about couple goals—coordinating fur trim for you and your love!

When I asked to know more about the page, he explained that the song featured was Gentil madona (spelled Zentil in the manuscript), composed by the Englishman John Bedyngham. Bedyngham was a refined composer whose beautiful and beloved part-songs followed the delicate 15th-century style. These pieces commonly had three different musical parts, which combined to create a gently undulating and subtly surprising polyphonic texture.

The lyrics of the song are somewhat mysterious, as they don’t fit into a simple poetic form. Scholars debate whether they were translated from English, French, or both. Below is one version of the text:

The following is the song in its original Italian with a facing English translation.

Gentil madona

Zentil madona

Deh non mabandonare

O preziosa gemma

O fior de margarita

Tu sei quella che tiene la mia vita

In tua guardia

de non my far morire.

La mya vita

In dolorosi guay finire

Perche ansi crudele sey en verso de my?

Tu scey ben che mirando el toy bel viso

Tu my festi de ty enamorare.

Gentle lady

Please don't abandon me

O precious gem

O margarita flower

You are the one who holds my life

In your safekeeping

Please don't cause me to die.

My life

To end in painful sufferings

Why are you so cruel toward me?

You know that, looking at your beautiful face,

You ensured that I would fall in love with you.

This song is certainly no “I Can’t Take My Eyes Off You” by Frankie Valli, but it is, like many love ballads, a heart-wrenching tale about how painful love can be. It is a cautionary song for those who hold the hearts of others. Clearly, these songs were popular and had a wide audience, as even a cleric wanted to sing about love! Fun fact: our own music library has a wonderful facsimile you can see for yourself!

Seeing the heart-shaped book immediately hooked me. Were there others? Was this common? Why don’t we have fun-shaped books as adults? To answer these questions, I turned to Professor Karl Whittington.

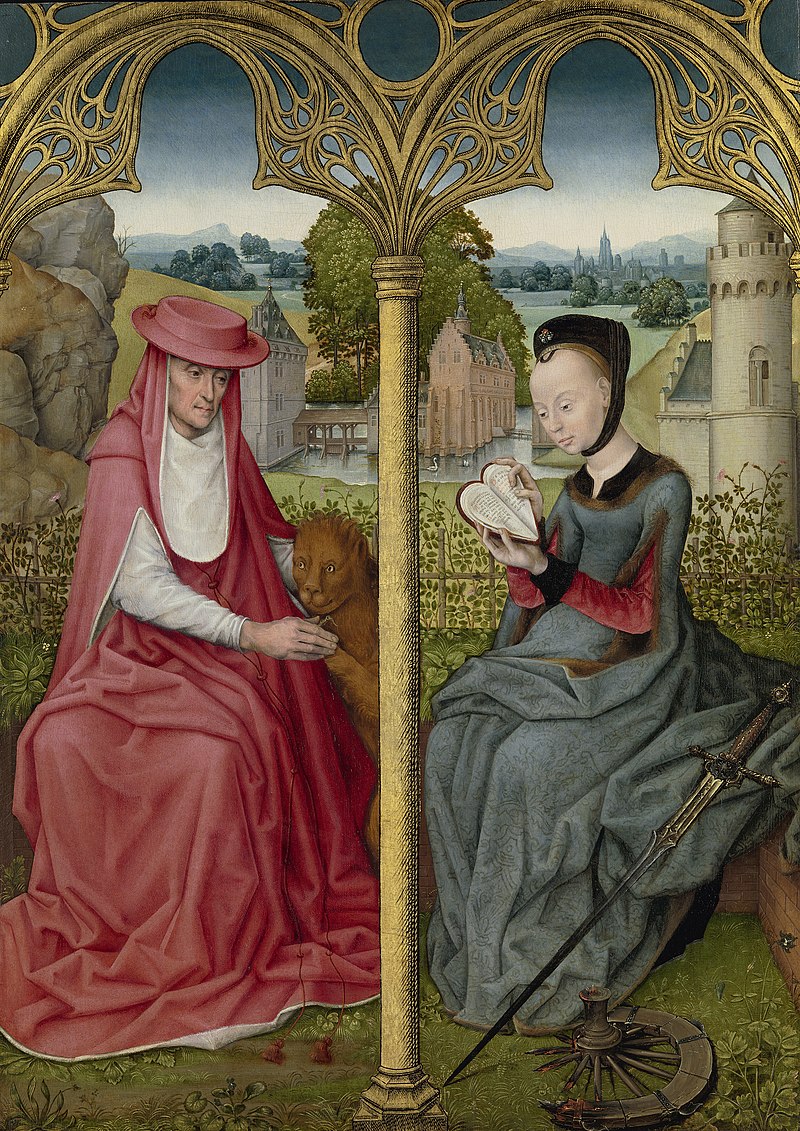

Professor Whittington explained that although non-square books rarely survive today, we have paintings that depict people using heart-shaped books. He pointed me to three paintings from Brussels, created in the 1480s and 1490s.

Two were painted by the “Master of the View of St. Gudula,” and one was by an unknown artist. While the books in these paintings look similar, their descriptions vary. The Met and the National Gallery suggest that the men in their respective paintings are most likely holding devotional or prayer books, while the Rijksmuseum speculates that the costly heart-shaped book held by a woman likely contains profane love songs. I like to imagine that maybe she was reading some early Romantasy! Whether sacred or secular, these books were clearly popular enough to appear in multiple paintings.

So far, I had looked at collections of songs and beautiful high-resolution images, but as many of you can attest, there is nothing like the smell of dusty old tomes. With that, I headed to the Rare Books and Manuscripts Library at OSU to see what treasures our own collection held. Our curator, Eric Johnson, is always enthusiastic about having people engage with the collection, so he was happy to provide a list of several items for me to examine.

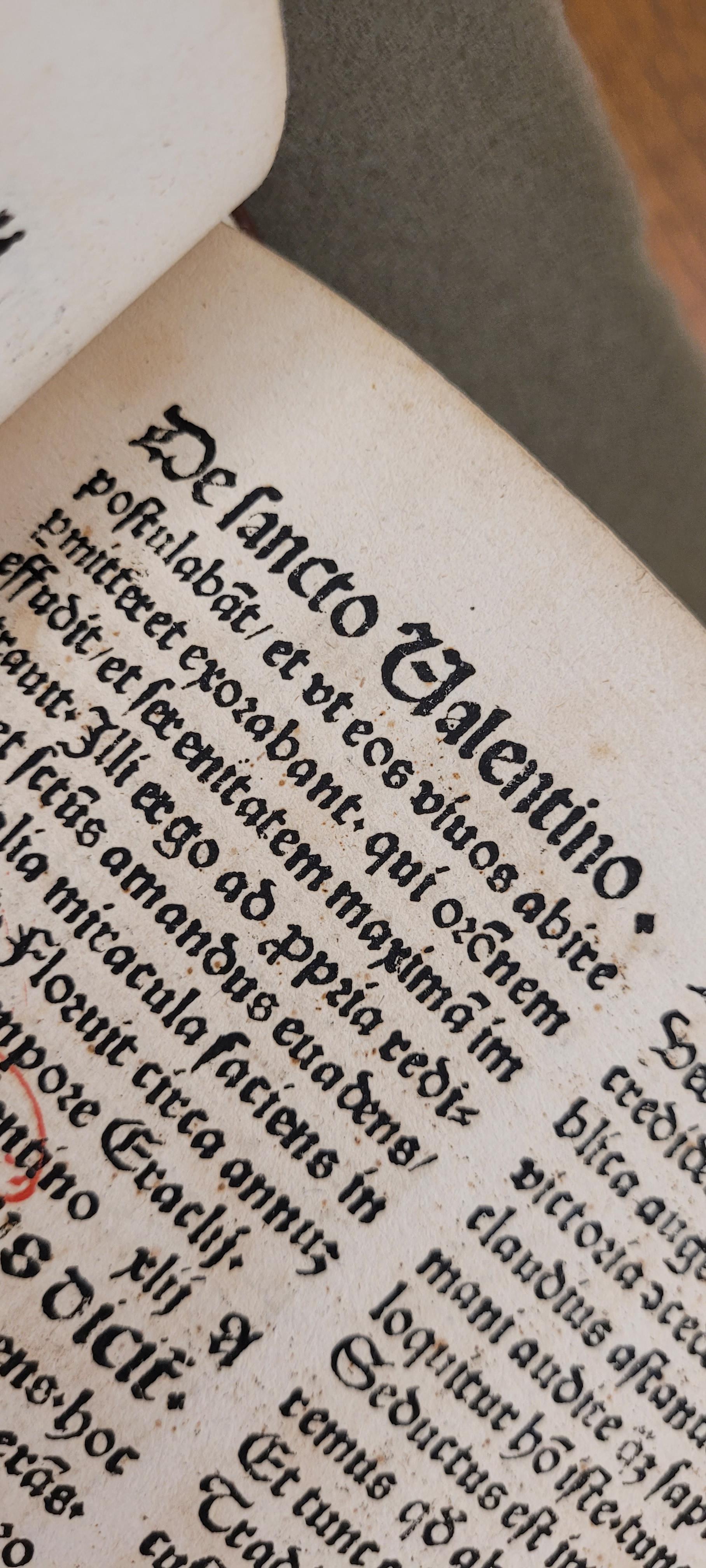

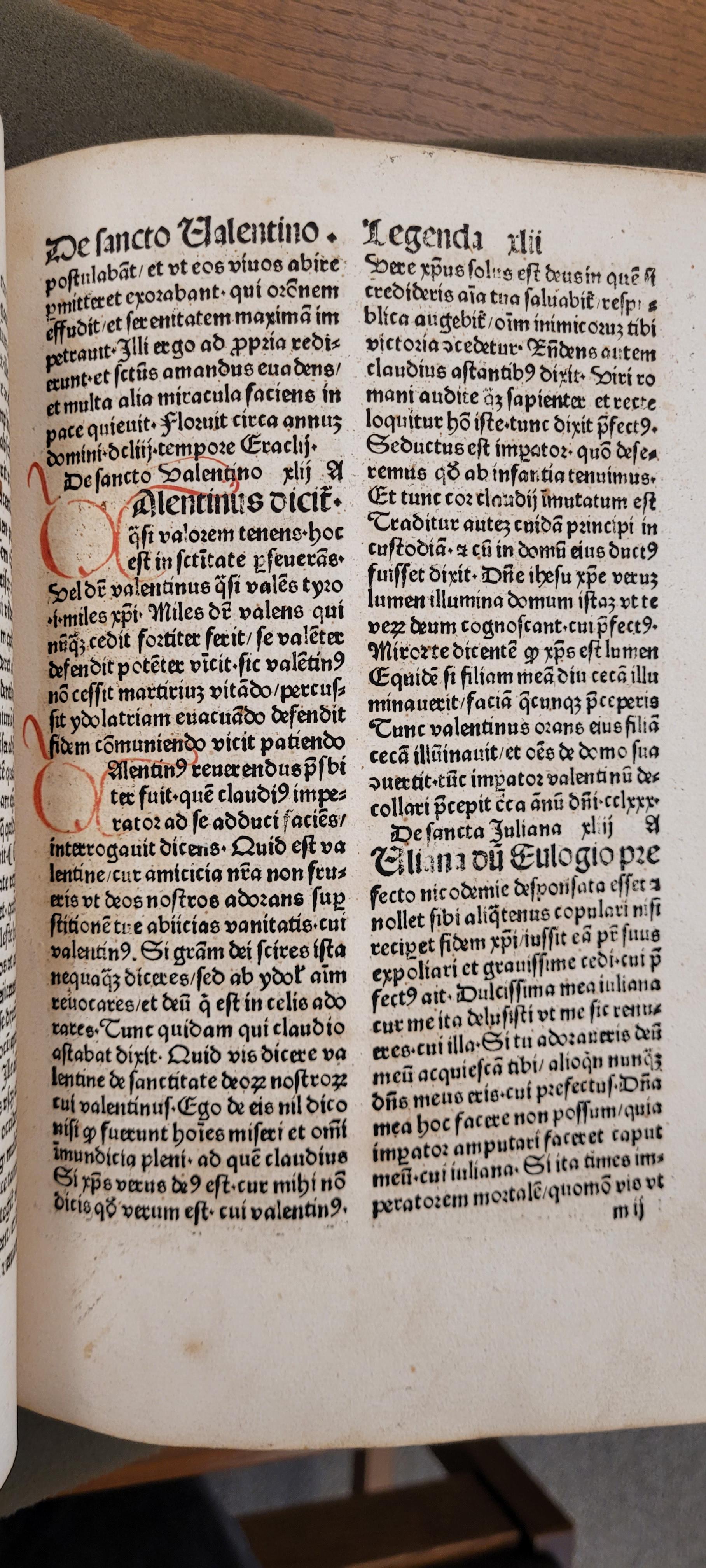

The first item features the name of a pretty well-known guy who is very connected to Valentine’s Day: Saint Valentine himself. This 15th-century bestseller is a printed copy of Jacobus de Voragine’s Legenda aurea, or The Golden Legend, a collection of the lives of saints. Our copy, which is in remarkably good condition, includes a complete life of St. Valentine. However, this story actually has nothing to do with marriage. Instead, his miracle is curing the blindness of a young girl, thus converting her and her whole family. Yet today we are often told that St. Valentine defied a Roman emperor and is now the patron saint of love and marriage.

The next item Eric pulled was indeed a depiction of a marriage. Perhaps the most famous married couple in the Bible, this fragment from a Book of Hours from Rouen, France, ca. 1475, depicts the marriage of Mary and Joseph. The incredibly rich blues and reds in the border decorations match the classic blue outfit Mary is often depicted wearing. However, upon zooming in, I wouldn’t say that the newlyweds were gazing into each other’s eyes with intense passion, so I asked Eric if we had any items that depicted couples who looked in love.

One particularly fascinating item was a fragment from a mid-14th-century French antiphonal. The margins are filled with wonderful tiny images, including a balcony scene where a man calls up to his lover and another of a couple in love, their faces turned toward each other, perhaps about to kiss. Maybe these are the types of scenes the lady reading her heart-shaped book was imagining?

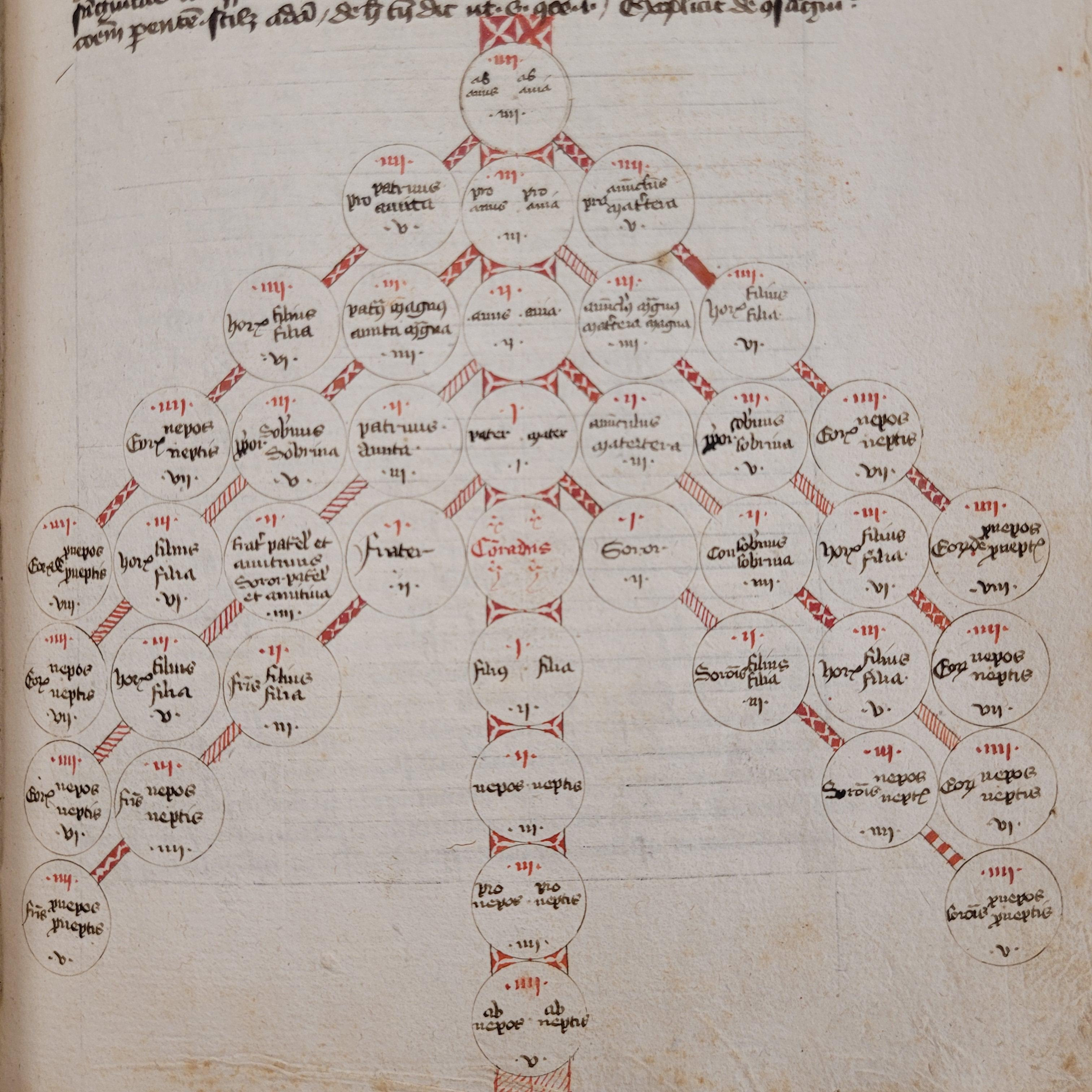

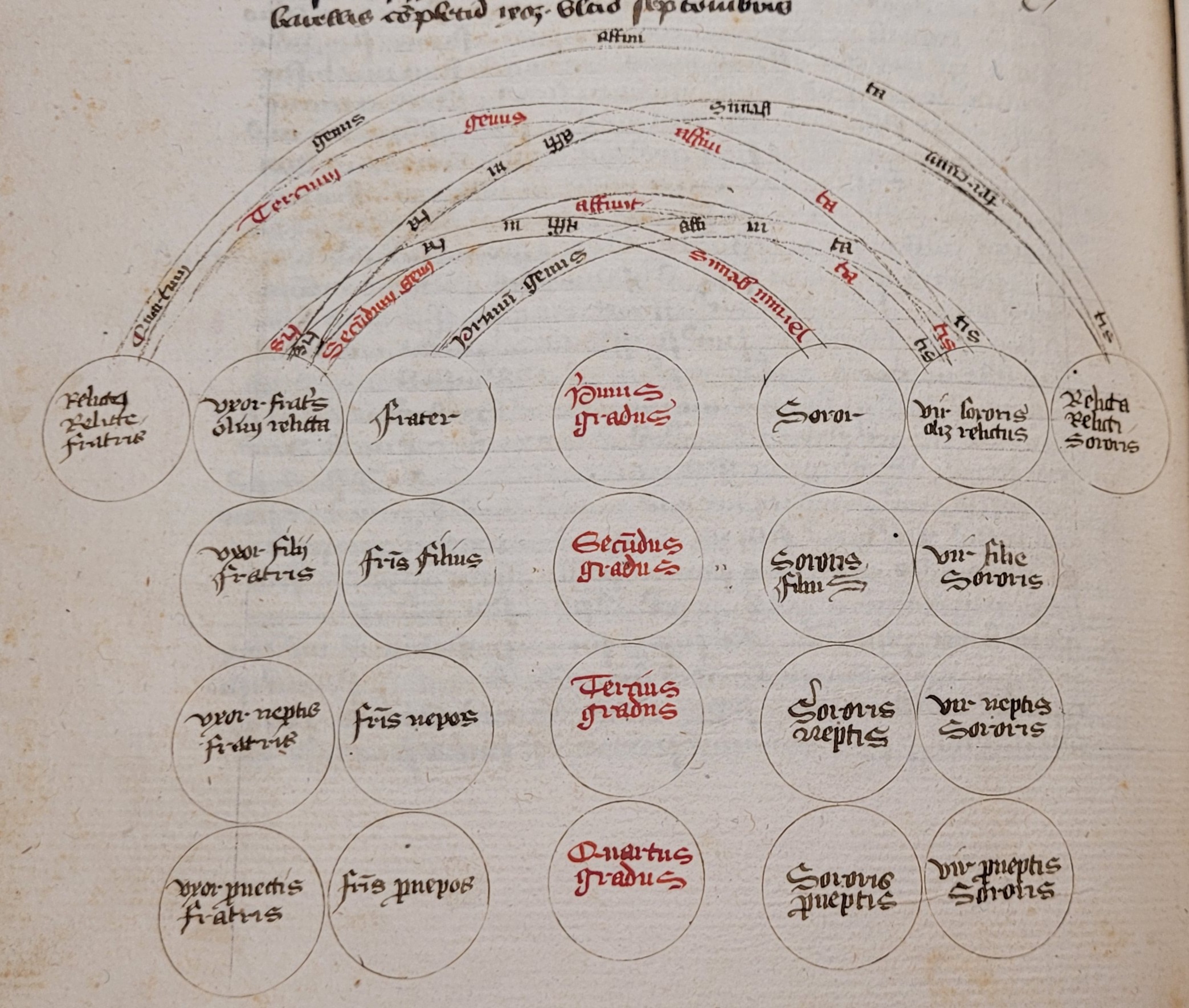

The last item Eric brought out was a codex of Francesco Zabarella’s legal commentary, De matrimonio, which discusses everything related to sex and marriage. Specifically, it includes tables of consanguinity, which display the degrees of relation between individuals to clarify prohibitions on marriage within one’s own family. These charts are certainly useful if you need to determine which cousins you can and cannot marry, but for most, they serve little practical purpose!

I thought then about other laws. Certainly, there are people you cannot marry. Are there days when you cannot? Are there certain restrictions on the ceremony or the dowry? To answer these legal questions, I trekked across the campus to Professor Sara Butler for all things legal.

I was excited because she originally told me that she would explain "Lovedays" to me. When I first heard the term, I assumed these must have been approved days for either marriages or the activities that take place within marriage. Or perhaps there were days deemed more auspicious for entering into marriage. After all, surgeons consulted the stars, why not matchmakers?

I found myself completely incorrect. Lovedays were not about the sacrament of marriage but rather about baptisms. They were planned mediations between parties with the goal of finding a suitable compromise. These mediations were often strategically scheduled to coincide with baptisms, another symbolic moment when people were freed of their sins and reconciled to God and the community. If they did not happen on a baptismal day, they were usually held on feast days when fighting was discouraged.

Professor Butler noted that this was particularly important in the British Isles, where more than one legal system was in place. On the borders of Scotland and Ireland, someone could easily find themselves on the wrong side of both the border and the law. This explains why Lovedays often included the exchange of prisoners. However, these occasions were not necessarily tied to a singular crime. Instead, they were a means of resolving multiple disagreements or disputes at once. Although not inherently romantic, there is a certain kind of love in restoring peace.

Clearly, across campus, love means many different things. While most of these works do not explicitly deal with St. Valentine, they showcase the many ways love has been discussed and represented throughout history. Whether through poetry, song, or beautifully crafted books, love is an enduring and multifaceted concept that has captivated people for centuries.

If you are interested in viewing the items from RBML (Rare Books & Manuscript Library) here are the call numbers:

Life of St. Valentine – INCUN.1488 J3

The marriage of Mary and Joseph - Spec.rare.MS.MR.Frag.509

De matrimonio - Spec.rare.MS.MR.Cod.56